Estimating agent-based models

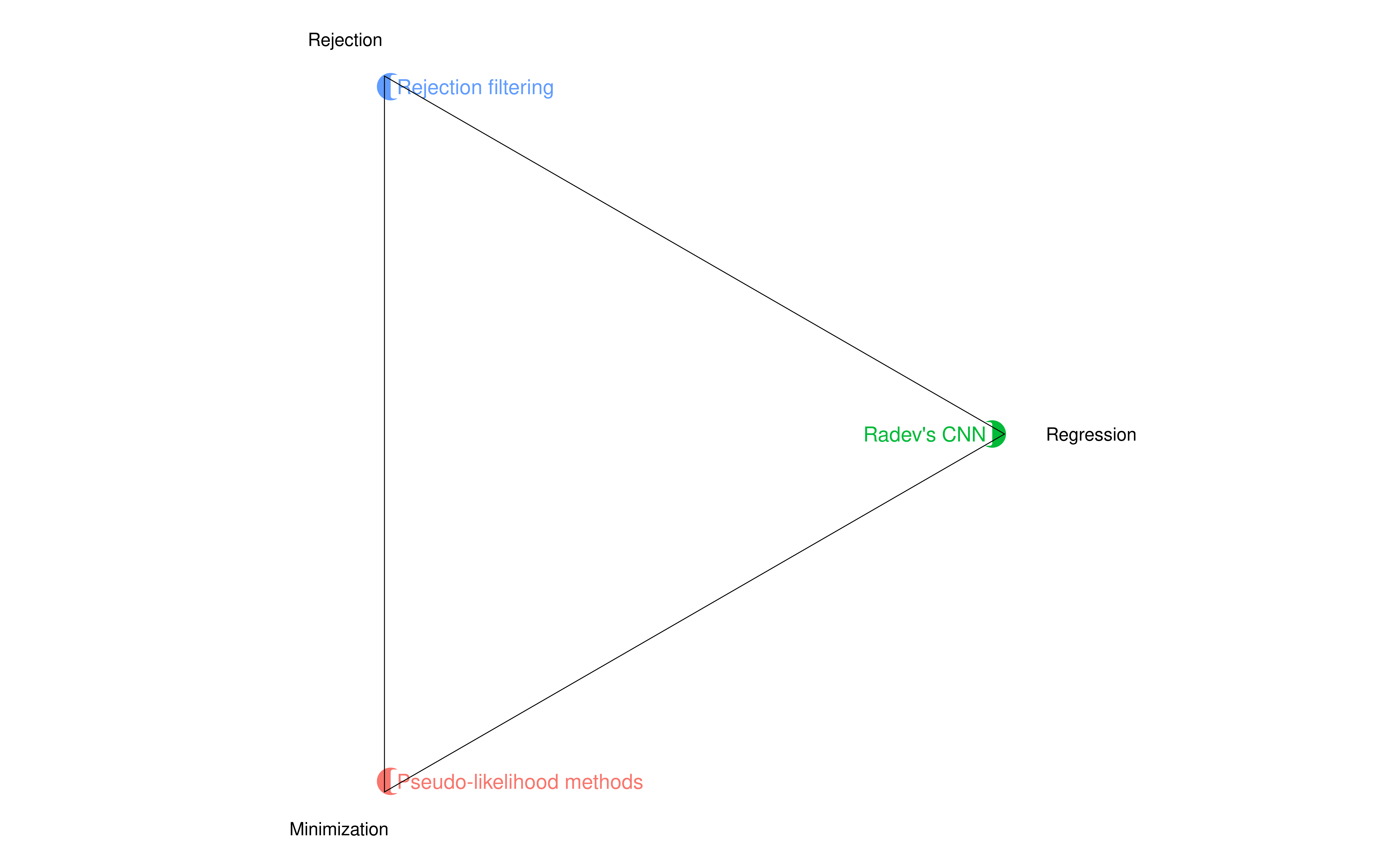

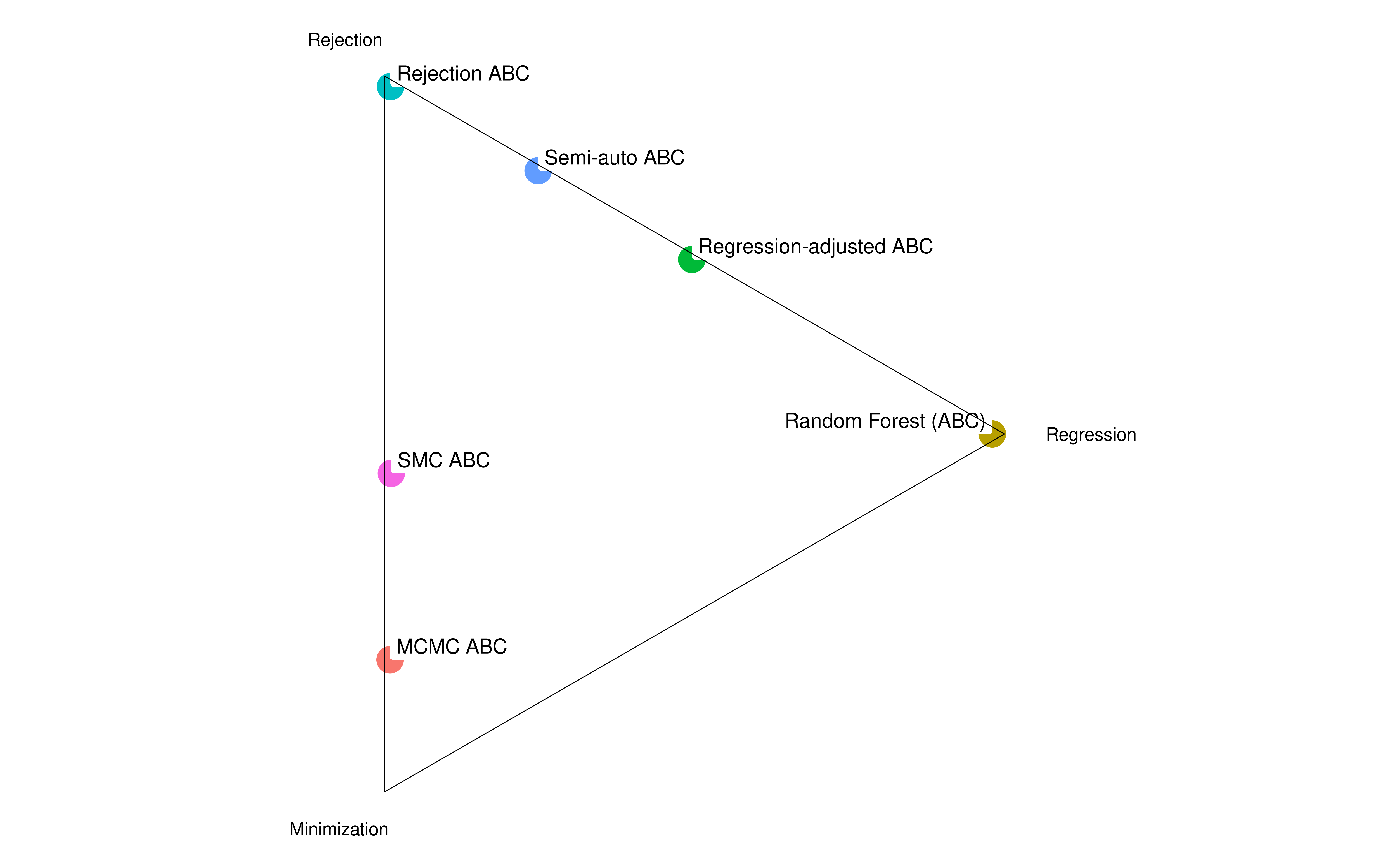

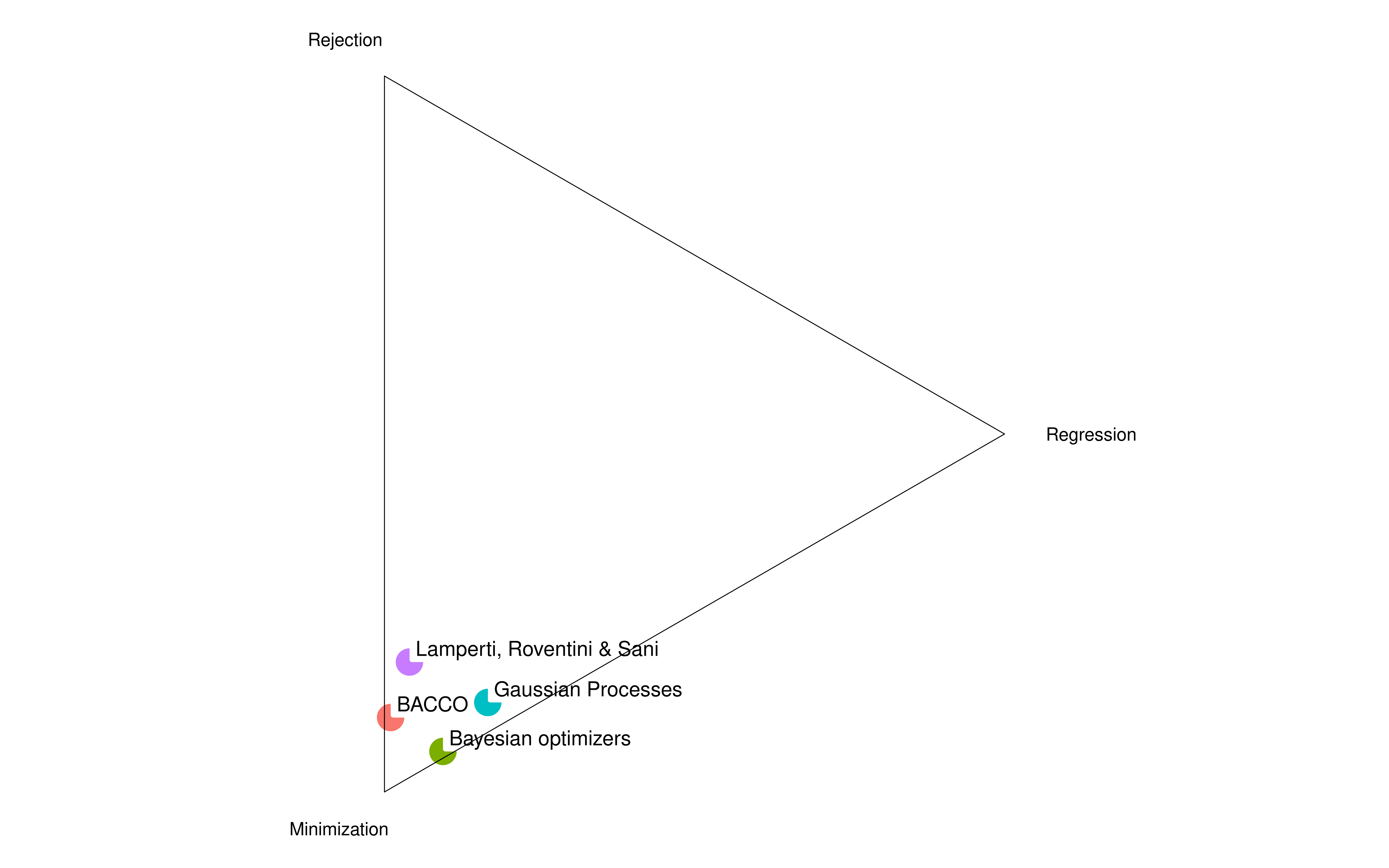

Estimation triangle

When you try to cluster estimation methods in agent-based models by “technique” (rather than statistical justification) you can really boil them down into three groups:

- Minimization: you change parameters trying to minimize the distance between model output and data (or maximize a likelihood function)

- Rejection: you run the model with random (possibly out of a Bayesian prior) parameters and then you accept all combinations that output stuff “close enough” to real data

- Regression: you run the model with random parameters and then you map the model output back to the parameters that generated it through a regression.

So the pseudo-likelihood examples for animal tagging in Hooten et al (2020) would be a good example of the first group; rejection filtering as described in Hartig would be a good example of the second; Radev’s convolutional neural network a non-parametric example of the third.

Of course many methods sit awkardly in between. One impressive thing about the Approximate Bayesian Computation literature is that they really span the whole space, one way or another.

I also think it’s important to notice that using a regression or “machine learning” does not make the estimation technique automatically regression-based. Quite to the contrary in fact as many popular meta-model methods are really just distance-minimization methods that use a regression for efficiency or regularization.

Which method to choose?

I am working on a paper showing that, unfortunately, there is no best estimation method all the times (quite to the contrary, for any estimation algorithm you can find at least one example where it is the best).

That however is only a limited view on the topic. A better way to think about which estimation method to pick is to notice that in reality there are many different objectives and some methods achieve them (on paper, anyway) better than others.

Efficiency

Often what we care about is to run the model the least amount of times to get the parameters. Or alternatively, get the best possible fit given a fixed computational budget. In theory, this is what maximization methods do better. This however comes with two caveats.

- You end up paying for the gains maximization grants you here when it comes to cross-validation.

- If your distance function isn’t well thought-out (or even just not well weighted) the efficiency is reduced. And experimenting with different distance functions require starting the minimization from scratch.

Confidence intervals

Point estimates can be helpful, but often we want some intervals around the “best” parameters. This can happen for many reasons.

- In economics people often assign deep meanings to parameters (usually as they hold the key to measure some opportunity cost that feeds into a cost-benefit analysis) and want to know how confident we are about those value (the ABM community doesn’t seem as enthralled by their own models, fortunately).

- We might need to perform some kind of hypothesis testing

- We are setting up a sensitivity analysis (ideally an ANT) and we want to bound our exploration ($\pm 10$% is not a universal empirical physical constant, yet!)

This is something rejection methods produce naturally. It is also a nice by-product of Bayesian methods with the added benefit that comparing priors and posteriors quickly hints at estimation problems. Some regression methods also do this neatly (in general anything that produces prediction intervals, so yes for Random Forests but no to lasso)

Inverse generative social science

A term I heard at SSC2020 but I am already spamming, IGSS means picking not just the best parameter vector nor an interval around them, instead picking the set of all parameter vectors that are “good enough”. Already by describing the definition it is clear that rejection methods already do this. The main difference is in terms of focus. We don’t care about the parameters that are accepted, just their combinations (usually to get a good handle on policy analysis and its uncertainty as a whole).

IGSS seems to be currently enamoured of non-parametric exploration through genetic programming. Of course this will explore many model forms in a way that parametric rejection will not, but I still see this effort as somewhat misguided.

Producing acceptable scenarios is nice, but what we want is to assign likelihoods to each of the accepted scenarios. That’s really the only way to use some form of central-limit theorem for policy analysis.

Bootstrap some distance function

The concept of distance between the model and reality is at the core of the minimization methods, but is often implicitly also part of rejection methods as well.

The problem is that complicated models like ABMs tend to have many ways they can be compared with the real world. That is, we are in a situation where there are very many summary statistics and we want to choose them carefully (and weigh their importance even more cautiously).

This kind of problem tends to wreck havoc with both minimization methods (very sensitive to weighing and picking a bad summary statistic or two) and rejection (since the computational load increases drastically with the number of summary statistics).

This is where regression methods tend to shine. Don’t bother trying to pick summary statistics manually, just let a regression pick them for you. This can be in support of a classic rejection (think semi-automatic ABC) but it doesn’t have to be an intermediate step. The regression can be used to do the full estimation. I’ve suggested using LASSO in a recent paper.

Check for identification (cross-validation!)

Take here Horowitz definition of identification: is there a one-to-one or many-to-one mapping between data and the model parameter?

In ABMs it is almost always impossible to tell a priori. In fact many estimation methods won’t reveal identification problems at all: minimizing distance between model output and reality will result in a point estimate even for parameters that are not identifiable.

Many ABMs are not remotely stationary (let alone ergodic) and it’s hard to imagine them being easily identifiable. Now of course you can take the position of Grazzini & Richiardi that a model that doesn’t have ergodic parts is a model where “everything can happen” and therefore useless, but I don’t really agree.

Rather we should take a pragmatic look at this. Most ABMs will have parts that won’t be identifiable. In my opinion this can be dealt with in three steps:

- We need to notice and catalogue what is identifiable and what isn’t.

- We need to do sensitivity analysis for all parameters that were not identified. ABMs, especially very descriptive ones, often have multiple mechanisms that accomplish the same task (inertia in agricultural models spring to mind) and in those cases we have some form of partial identification (we know there is inertia but can’t tell the source) which isn’t a deal breaker for many policy suggestions.

- We either move toward IGSS and study the group of accepted parameter vectors as a whole (the inevitable consequence of non-identification) or invent data/experiments that would achieve identification and then go out and collect it for real.

The point here however is that we need to achieve step 1. The only real way to do it is cross-validation (wide posteriors in ABC are a warning sign, but not hard proof).

You need to treat your model output as “real” data and then make sure your estimation technique can get it back. The cost of it is trivial for rejection methods (just need to generate the testing set) and regressions (unless you are re-training them in block which is a bit more expensive) but it is massive for minimization methods (chi semina vento, raccoglie tempesta).

Still, it has to be done. So get on with it.